Campus Avenue bears a strange energy, intangible, ethereal. Halfway between the Administration Building and the Lower Dorms, six ancient stoneworks line the road. They are arranged the same way as the pips on the six side of a die, even rows with a gap between, where the brick road runs.

The pedestals are four feet off the ground at their highest, each with a low ramp that runs to the edge of the road and no further. The road is not part of them, since the stoneworks were constructed from a form a basalt known only to exist miles below the surface. The road is red brick only. The road is not special save that when it was built, the road crew specifically, carefully, painfully measured the spacing between the pedestals that they should avoid the road sides from touching the edges of the stone ramps.

Nobody had asked them to. That is what everyone knows about Campus Avenue: nobody wants to disturb the stoneworks. They are scarcely documented. The university’s most prestigious archeology team had determined little, except, “they are there, and have been for a long time.”

All historical records which have ever mentioned the stoneworks said more or less the same.

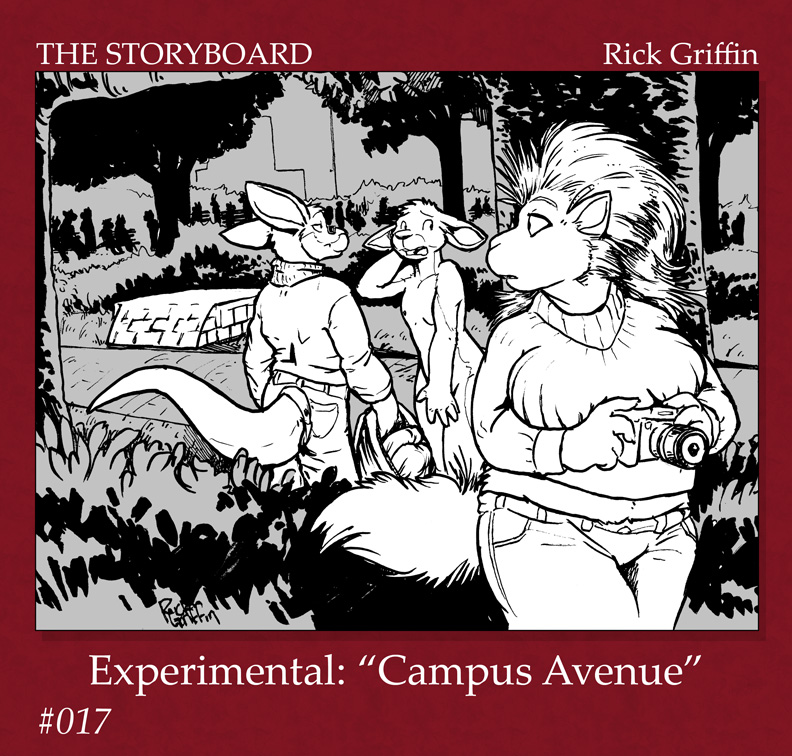

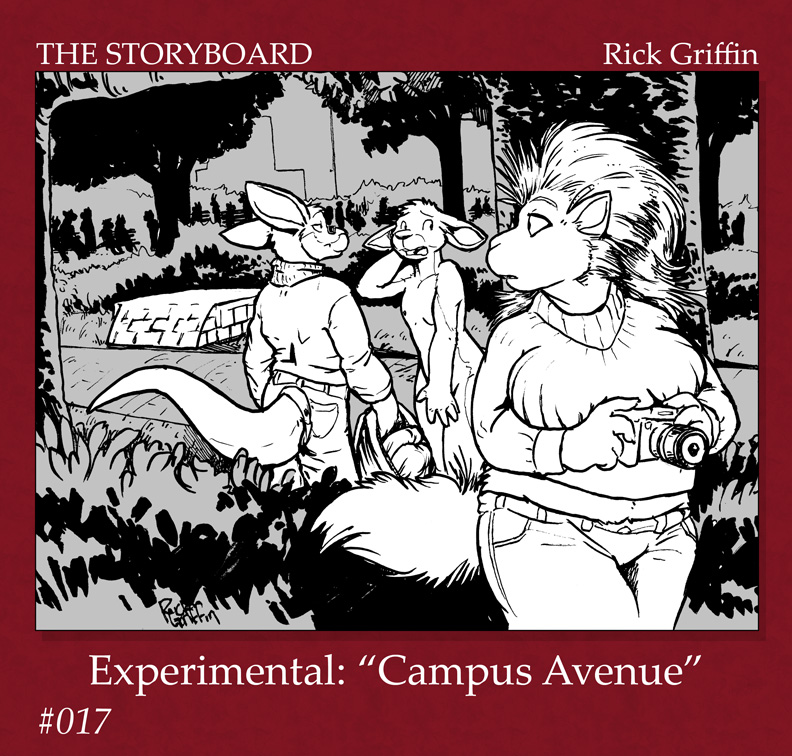

When the university was founded, they situated benches around Campus Avenue in a radius, the space all between filled with shrubs and trees, rarely tended to be groundskeepers. The benches are always full, with more standing beside. The place transfixes people. At a respectful distance, students discuss campus life, classes, work and money, and with an easier, calmer, and more relaxed tone than anywhere else.

Though little can be said about the stoneworks academically, what have been passed around are the rumors, which become stories. They are also spoken in the circle around the avenue. And so, as universities are wont to do, it became a tradition that incoming freshmen had to walk down the avenue between the pedestals at least once.

Naked.

Reed stands uneasily at The Line. Reed lived up to his name, being reedy for a kangaroo, russet in color with white belly, arms and legs, and perpetually anxious, as though the early-autumn wind shook him. His clothes removed, he is down to his skivvies. He rests on his large feet uneasily, rocking them back and forth, until Clay takes him by the arm.

Clay, also a kangaroo, holds Reed’s bookbag, stuffed with Reed’s clothes, and also his own bookbag. Clay smiles at Reed, his darkened muzzle tips emphasizing the movements of his face. Reed considers: that Clay is putting him up to this, but also that Clay is his dearest friend.

“This is stupid,” Reed says, looking down where The Line ended at the tip of his long middle toe. The Line was so named because it was where the graffiti ended. As the rumors went, even a gang who had once spray painted the bell tower and pulled down the statue at the garden square stopped here and walked quietly through.

“A little, yeah,” says Clay, shrugging his shoulders. His gray fur and broad shoulders makes him appear older than he is, but only from a distance. When he opened his mouth, he didn’t sound any older than Reed; he is only one year Reed’s senior. He adjusts the rectangle-rim sunshades that rest on the flat of his muzzle. “They’re just some old rocks. Everybody makes a big deal about it, but if we stopped then there wouldn’t be as much significance. Most of it’s just in your head.”

“But that’s just it. It’s not the stone things, it’s that everyone’s watching.”

From their vantage point on the road, only a few people are even visible beyond the green shrubs and trees. Yet the two had just been back there when Clay proposed the idea. There were at least a hundred students milling about in the mid-afternoon, mostly doing homework or messing with video streaming on their phones. They didn’t even take any drugs or alcohol around this place; it “felt” unnecessary, though Reed could not determine why.

It wasn’t that Reed didn’t know why he was doing this—he did it because Clay asked. And when Clay asks, Reed would do anything.

He owes it to Clay. Reed doesn’t have the words to say why, though it was a common enough feature of his whole life it is merely how he “is”. Words always stick in his throat, unsaid in part because he cannot get his thoughts to behave, and he dismisses them. Yet the unspoken lines wheel away somewhere in his forgotten mind.

“They’re not even paying attention,” Clay says.

“Yes they are,” says Reed.

“Then imagine them in their underwear.”

Reed stares daggers at Clay as he stuffs the remainder of his clothes in the bookbag. There wasn’t much use protesting, besides now being cold. Reed was only somewhat trim, mostly due to late growth spurts at the end of high school, though he was still naturally heavy around his waist. Being naked bothers him mostly on an intellectual level. He tries to casually cover his maleness with one hand, though the whole arm ends up stiff and awkward in the attempt. He stares again at the end of The Line.

“The sooner you get across, the sooner you can get your clothes back on,” says Clay as he urges Reed with a gentle shove on his lower back.

Reed awkwardly steps over the line. Almost as awkwardly, he turns, facing Clay, and grabs his hand.

“Please come with me,” Reed says.

There were reasons Clay could object, primarily because it was tradition for freshmen to walk alone. But Clay must have felt the trembling in Reed’s hand. Without hesitation, he nods, smiles, and drops the bookbags just over The Line.

Reed’s hand bashfully releases Clay’s to let him undress. They’d been friends since elementary. But Clay had been there when Reed’s father died, and something had changed between them. Though Reed would do anything for Clay, he often works himself up into fits of anxiety, thinking this time he’s asked too much of his friend. He twists in his place and runs his hands through his head fur.

If he’s asked too much of Clay, Clay has never said. Clay smiled warmly, as he always did, and put Reed back at ease.

The last thing Reed would believe was that he deserved a friend like him.

Once Clay removed his sunshades and stuffed them into his own bookbag, he stands. Unlike Reed, his body is pitch-perfect in fitness, not merely by chance but by effort. It bred jealousy in Reed, in a way—only that he wished his own body could make things easier. What fun it would be to have Clay’s body! It would be easy to attract girls, maybe, and Clay probably doesn’t feel the least bit self-conscious about being in bare fur.

Clay gestures forward, and walks beside Reed with his arms clasped behind his back.

Reed barely even sees the first row of stoneworks as they pass, as he continues to shoot glances at Clay. They had been naked together enough times before that it should not bother him, and yet it does. Why did he ask Clay to walk with him?