Besides his own self-consciousness, Reed doesn’t feel much of anything. The road feels the same as the road before The Line. The grass is just as green, the wind just as bitingly cool. Time didn’t speed up or slow down, and the anticipation in Reed’s chest doesn’t give way to any “release” that he anticipated.

“Bit of a let-down,” Reed says.

“I said it was a bit boring,” Clay says.

“But there’s all the stories. I mean, they don’t make any sense and they are, without exception, self-contradictory. I thought maybe there was something about this place that would fuel it.”

“Like what?”

“Well, there’s the one time a lion was overcome by the energy, stood on one of the platforms and transformed into a lioness. I think that’s pretty big.”

Clay points it out, the middle stonework on the left side. “That one. And she was always a lioness. Says so on her school records.”

“Then why does everyone say she was a lion before? I mean, you even know which platform it is.”

“It happened before I enrolled,” Clay says. “But that’s mythology … It evolves, the little details become sticking points, and give details to make the story more real. This one is called Pedestal C, by the way.”

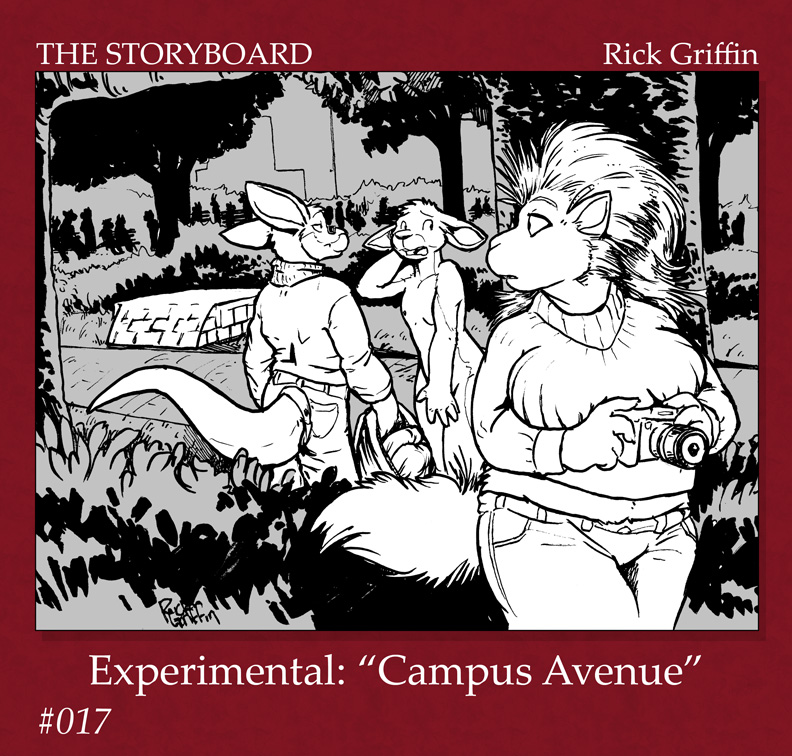

They stop in front of it. It looks the same as all the other stoneworks: simple and unadorned. No fancy carvings, no magic runes. They are made of very plain, very ordinary, very very old rock.

“It’s almost like the head of a piton that’s been hammered into the ground,” Reed says, stepping to each of its corners to get a good look. He hunches down for a lower angle.

“It’s almost what they are,” Clay says, “It hasn’t been measured exactly, but they reach a long way underground, and they taper.”

“So why would people just start attributing power to them, then?” asks Reed. “I mean, the stories have to come from somewhere. If she—”

“—Penny.”

“… You even know her name? If Penny were a lioness all along, why would anyone, let alone a constant swarm of witnesses, believe she was a lion before?”

“Well, maybe you could test it. You’re a science major, right?”

Reed stands back up and rubs the back of his neck. “Test it? Like … If I walked onto that platform, I’d become a jill?”

“What better way to try?”

“I don’t want to be female!” Reed says, squeezing his eyes shut at the line. He knows what it sounded like—too quick to protest; the words felt all wrong. Not that they are untrue, only that they were inordinately defensive.

“You’re not actually going to become a woman,” Clay rolls his eyes and folds his arms. “Just step on the platform.”

Reed’s heart jumps into his throat. He looks at that platform, hard, with eyes that could drill holes through mountains.

“Well?” Clay says

“I …”

Reed stops himself—he isn’t weak. He went two decades being weak, but he is older now. He is an adult, now far away from his family, save for Clay.

“Where’s that from …” Reed mumbles to himself.

He feels homesick, and it pulls him away from the stones. He turns from them.

“It’s a simple task, isn’t it?” Clay says, “Just step onto the platform.”

“Why don’t you?”

Clay sighs softly. “Because I know I can’t,” he says. “I’ve tried. Everybody does.”

“Then why do some people get on the platforms?”

“There’s a lot of theories … I’m not sure I believe any of them. But the one that I hear tossed around most often is that you can only step on a platform to receive something you desperately need.”

Reed considers. He wished for a great many things in his time, but he thought wishing to be impractical, especially as fear bolted him to the ground. He casts his eyes toward Clay again, noting his lithe body, and how envious he is of that body.

Clay smirks and opens his arms for a little pose. Reed blushes and faces away, fingers racing nervously through the fur on his arms.

“What is it?” Clay asks again.

“What if I just wanted a better body? One that I could be confident in. That’s something I know I want.”

“You can try.” Clay gestures to the platform.

Reed bites his lip and turns to the ancient stonework. He lifts his feet to the ramp again, and this time he falls back on his mental pattern of shoving the strange thoughts from his mind. He would not let those thoughts bother him; they will be buried somewhere far away, and he would never give them voice.

He stops.

Clay stands, arms folded, an amused smirk crossing his face.

Reed lowers his foot. He can’t push away the thoughts. His body contorts. He falls to his knees and curls his tail around his legs, face buried in his hands.

Clay’s tone suddenly turns panicked. “Reed? What’s wrong? Reed, what’s happening?!”

I remembered when my father died, I was inconsolable. I was so bedridden my parents thought me ill. And you came, and you did perhaps the same thing that my family had done—you embraced me, and you told me you’d listen, or stay with me, or do whatever I needed. But, importantly, that you would be there. Without even asking you made me the most important person in your life. As we sat in the dark at the foot of my bed, we played games on my TV, which had laid dormant until you came by. And I was still crying, but the endless nightmare stopped weighing me down. I became lighter. And you’d made me so happy, and I tucked my arm around your side, and you did the same. I wanted to be there forever, with you, who’d slew my demons.

You looked in my eyes.

And I looked in yours.

“Reed,” Clay says, stroking his ears, “You’re crying. Can you hear me?”